Our Nailsworth concert on Sunday 18th February featured Lili Boulanger’s D’un matin de printemps [Of a spring morning], alongside Fanny Mendelssohn’s Piano Trio. On 16th September we return to Nailsworth with her lively Cortége for solo violin and piano, alongside several pieces by Elgar.

In 1895, two things happened to two-year-old Lili Boulanger that would shape the rest of her life. Firstly she fell ill with bronchial pneumonia, which was nearly fatal and weakened her immune system, leaving her almost constantly ill thereafter, either with passing infections or with outbreaks of Crohn’s Disease. The other thing that happened was that the composer Gabriel Fauré, a family friend and later one of Lili’s teachers, discovered that she had perfect pitch.

It is perhaps not surprising that Marie-Juliette Olga Boulanger, always known as Lili, was born with musical talent. Her father (77 at the time of her birth) taught at the Paris Conservatoire and had won the coveted Prix de Rome for composition in 1835. Her mother, a Russian princess, was a professional singer. Lili’s older sister Nadia was also a promising composer who went on to become one of the most influential music teachers of the twentieth century, with students including Aaron Copland, Quincey Jones, Elliott Carter, Daniel Barenboim, Astor Piazzolla and Philip Glass. Before her fifth birthday, Lili would accompany Nadia (herself only 10) to classes at the Paris Conservatoire, soon sitting in on music theory classes and having lessons at the organ with Louis Vierne. She sang and played the piano, violin, cello and harp. She was taught composition firstly by her older sister, and later by Paul Vidal, Georges Caussade, and Gabriel Fauré.

In 1909, after Nadia had given up after four unsuccessful attempts to win the Prix de Rome, Lili decided to compete for it. She took private lessons with Caussade and attended Vidal’s classes at the Conservatoire, and entered the competition in 1912. She was unsuccessful that year, but the following year she competed again and made international headlines by becoming the first woman to win the Prix de Rome with her cantata Faust et Hélène. The prize was a publishing contract with Ricordi, the major Italian music publishers, offering her an annual income in return for first refusal on her compositions. She was also required to spend time composing at the Villa Medici in Rome. Although, after a bout of measles, Lili spent some time at the Villa Medici in 1914 (where she wrote the charming Cortège, one of her most popular works), her visit was cut short by the outbreak of the First World War (it also seems that her presence there, as the only woman, met with some hostility). On her return to Paris, she founded the Comité Franco-Américain du Conservatoire National, an organisation to support musicians fighting in the war. She returned to Rome in 1916, but her poor health cut this visit short too, and she was soon back in Paris.

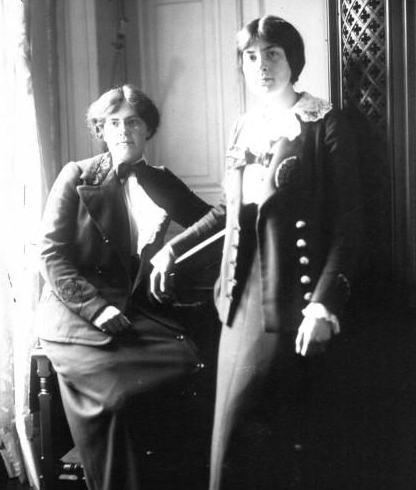

Lili’s health deteriorated and her last work – her Pie Jesu for soprano, string quartet, harp and organ – was dictated to her older sister during February and March 1918. Lili died on 15 March 1918, aged just 24. She is buried in the cemetery at Montmartre in Paris. Nadia lived another 61 years and was laid to rest in the same tomb in 1979, aged 92.

Lili Boulanger’s music was influenced by the style of her teacher Fauré, and draws on Debussy’s impressionism, as well as referencing plainchant, modes, and some of the avant garde ideas that were starting to appear in the early twentieth century, but always within a tonal framework. Her compositions are often beautiful and delicate, though many have an air of melancholy. D’un matin de printemps, however, is fast and lively, standing in contrast to its slow companion piece D’un soir triste [Of a sad evening], with which it shares some musical material and ideas. Both works were started in the spring of 1917, about a year before Lili’s death. D’un matin de printemps exists in three forms – a version for piano trio (which we will be performing), another for flute or violin and piano, and an orchestral version completed just before her death.

In her lifetime, Lili was defined as much by her ill health as by her gender. This tall, elegant, but frail young woman defied expectations by creating confident and ambitious music, often for large forces, with an energy and passion that was sometimes described as ‘masculine’. Lili was hugely talented but also worked extremely hard both at her composition and in her business dealings and social life. She was fully engaged with the world, taking a keen interest in the war and its repercussions, and this is reflected in many of her works and in her actions. That, rather than the ‘poor little thing’, was the true Lili Boulanger.